Expositions are the timekeepers of progress

Prospectus PDF -available here-

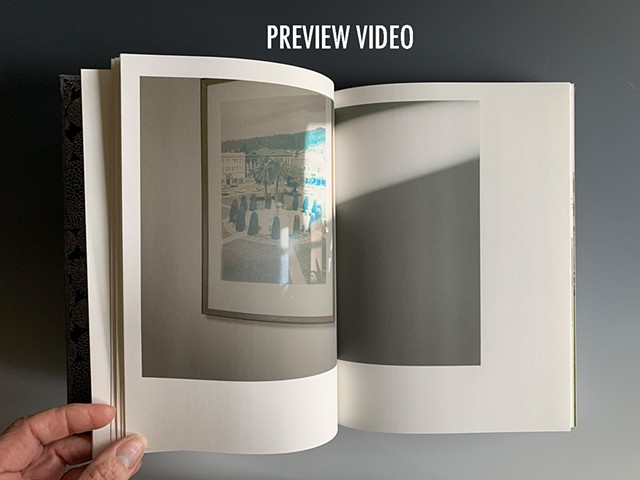

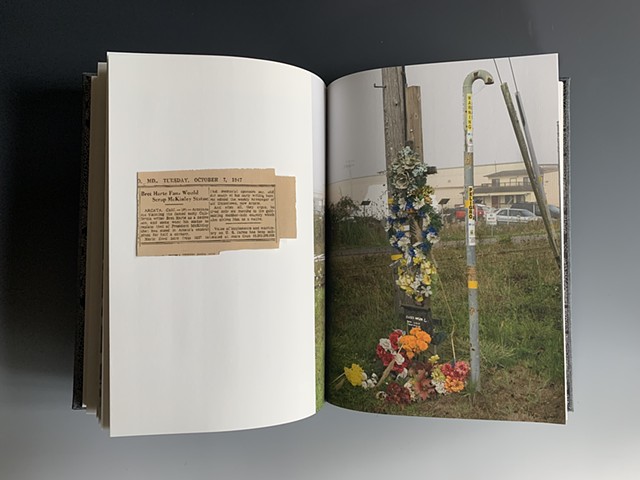

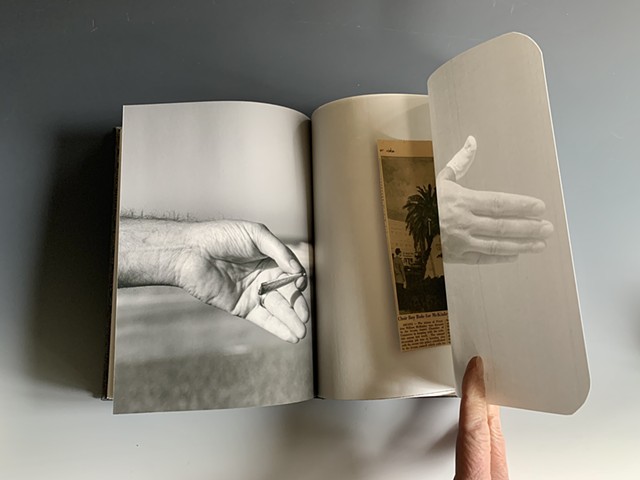

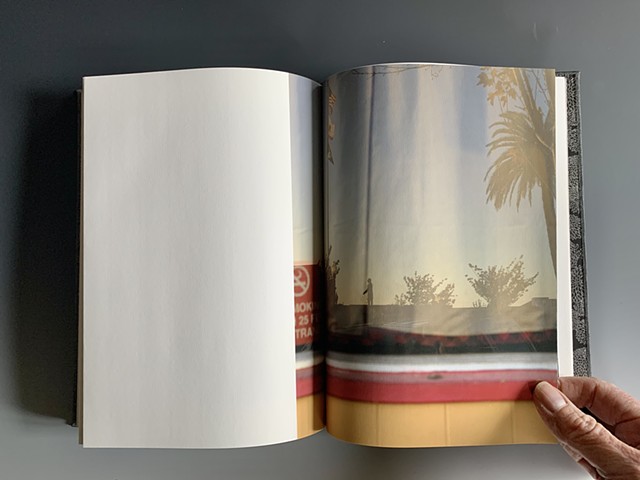

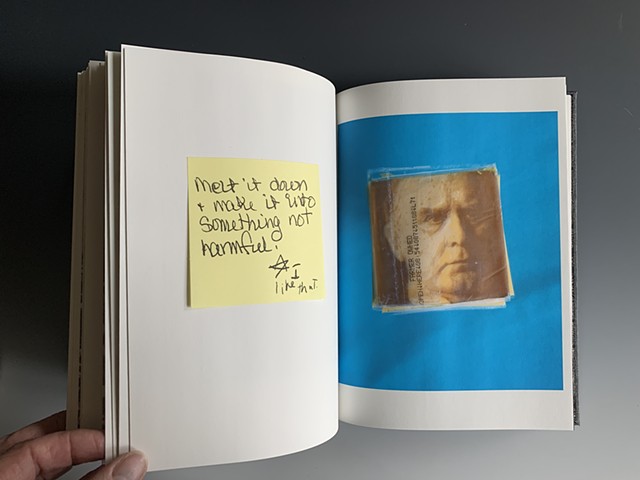

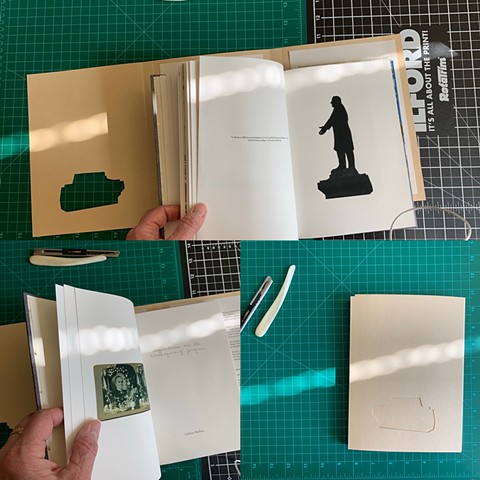

This work is a poem about removal and mass misinformation. It is an examination of the issue of monument removal in the United States, though the story of one town, and the effigy of a president who never belonged there in the first place. Conceived as a book, due to the complexity of archival material and multi-faceted storytelling, the breadth of pictures is interwoven with a visual social history of the statue. It asks the viewer to question if they are looking at a document or a para-fiction, as the town did in grappling with its decision.

At 4am on February 28, 2019, after a long, contentious battle, an election, and a rainy winter, a statue of President William McKinley was disassembled and taken from the town plaza of Arcata, California. It was the first Presidential statue removed from public view in US history.

On one side of the removal debate, were a vociferous group of activists who called the 25th President a racist, and slave owner who did not deserve to be in their town. On the other, those with fervent nostalgia, who also resented a town council that did not seek a vote of the people. But the point of interest that drew me to follow this story for over a year and all the way to Ohio (where the statue is now in storage) was that in truth, neither side seemed to have any idea what exactly McKinley did wrong, or that he had fought for the Union in the Civil War. Many thought the effigy in the square was a logger, as there is a town called “McKinleyville” five miles north.

Over the 100+ years it was in place, the statue was climbed by jubilant students from the local university, defaced with caustic substances, had cheese stuffed in its nose, had its thumb sawn off (later recovered and re-attached), and decorated for holidays as everything from a choir boy in white-face to an angel. None of these acts have had anything to do with the president himself. The statue was a talisman; a mountain; a meeting place. It functioned not as a symbol of white oppression of the native Wiyot, nor the imperialist tendencies of the president himself, but simply as a mascot. Yet, the robust conversations in the community, taken slowly and methodically, helped all sides to see each other, and led to a previously improbable act of neighboring Eureka, returning Wiyot land, stolen in 1860 after a brutal massacre.

Click on images for more information and to purchase.

Edition 7 + 2 A/P (4 available)

Public Collections:

Hirsch Library, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

University of Arizona

University of Colorado, Boulder

Awards:

2022 MCBA Prize, Semi-Finalist